Published Animal Locomotion and Paved the Way for Motion Photography

Guest blogger Maggie Hoot is a Smith Higher student, grade of 2016, with a major in Art History. She is a Student Assistant in the Cunningham Middle for the Study of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

In 1872, old California governor, railroad tycoon, and subsequent college founder, Leland Stanford wanted to prove the hotly debated hypothesis that at that place was a bespeak in a running horse's gait when all 4 anxiety would exist off the ground at one time. He hired a locally famous British photographer named Eadweard Muybridge to exam the hypothesis by photographing his horse, Occident, in motion. At this time, photographic applied science was not avant-garde plenty and consequently Muybridge could non capture a definitive image.

Five years subsequently, Muybridge returned to Stanford's ranch with improved equipment to try again. He was finally able to take a clear series of photos and proved Stanford right. This set of photographs of Stanford's equus caballus, Sallie Gardner, became an instant sensation and Muybridge'due south photographic career reached new heights. Muybridge spent the next seven years touring the United states of america and Europeshowing his photographs and lecturing on both photographic technologies and new research related to animal locomotion. He presented his work on a zoopraxiscope, the first auto capable of large-scale projection, which Muybridge himself invented. Muybridge based his invention on a children's toy, the zoetrope, a handheld spinning pulsate that produces the illusion of motion, and used a lantern to projection the image onto a screen.

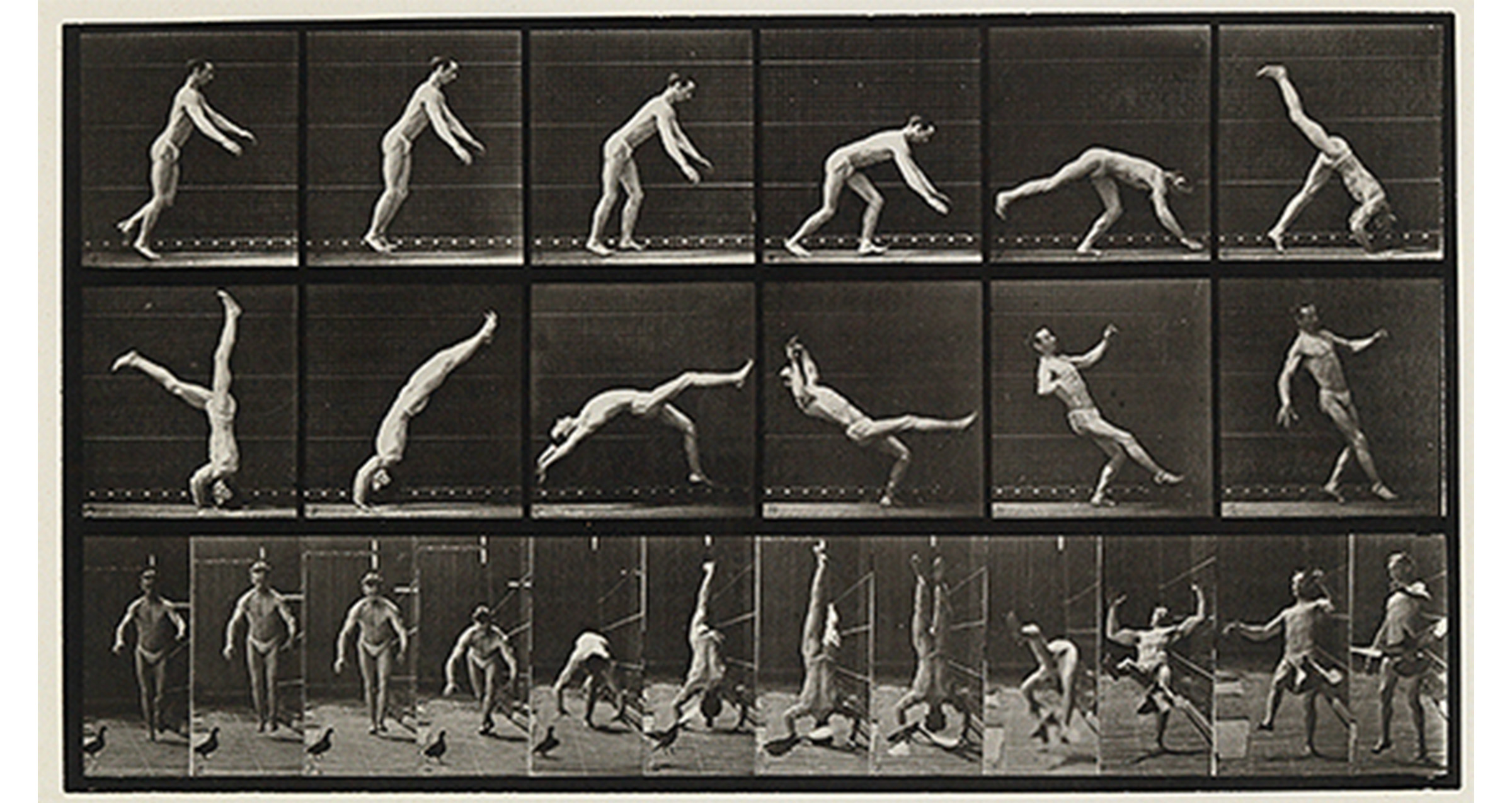

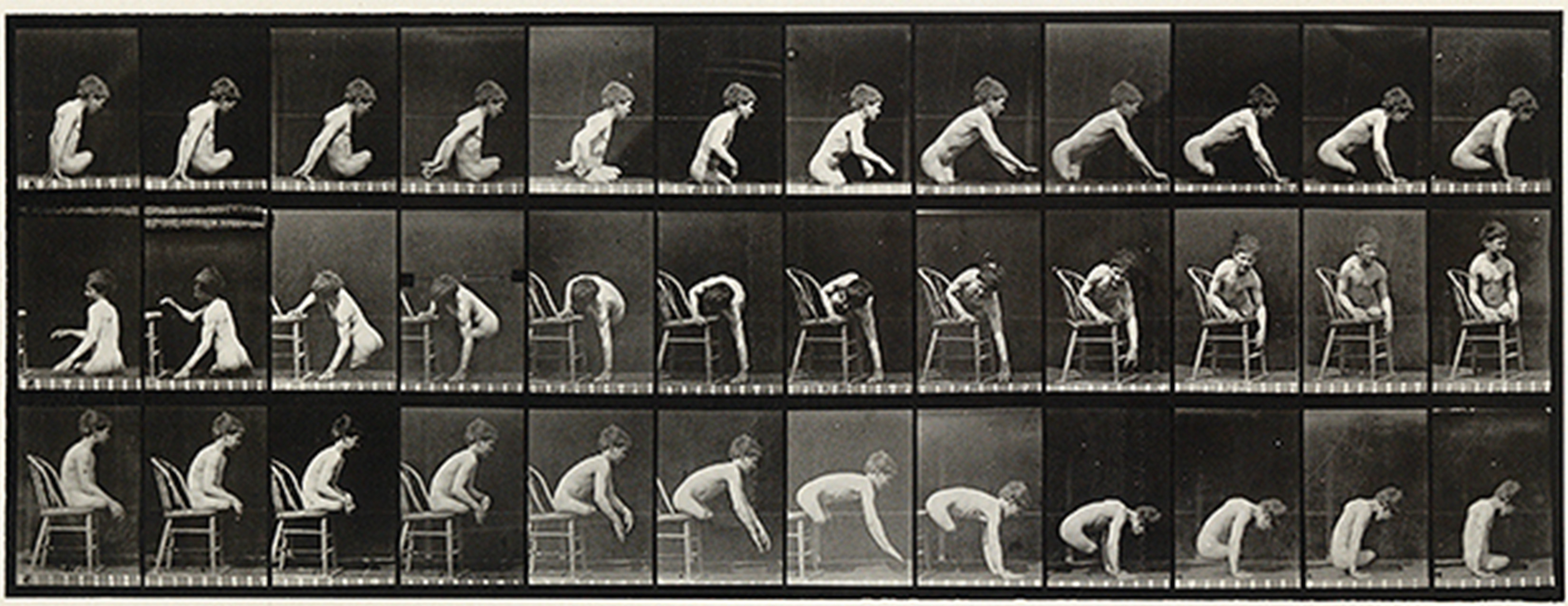

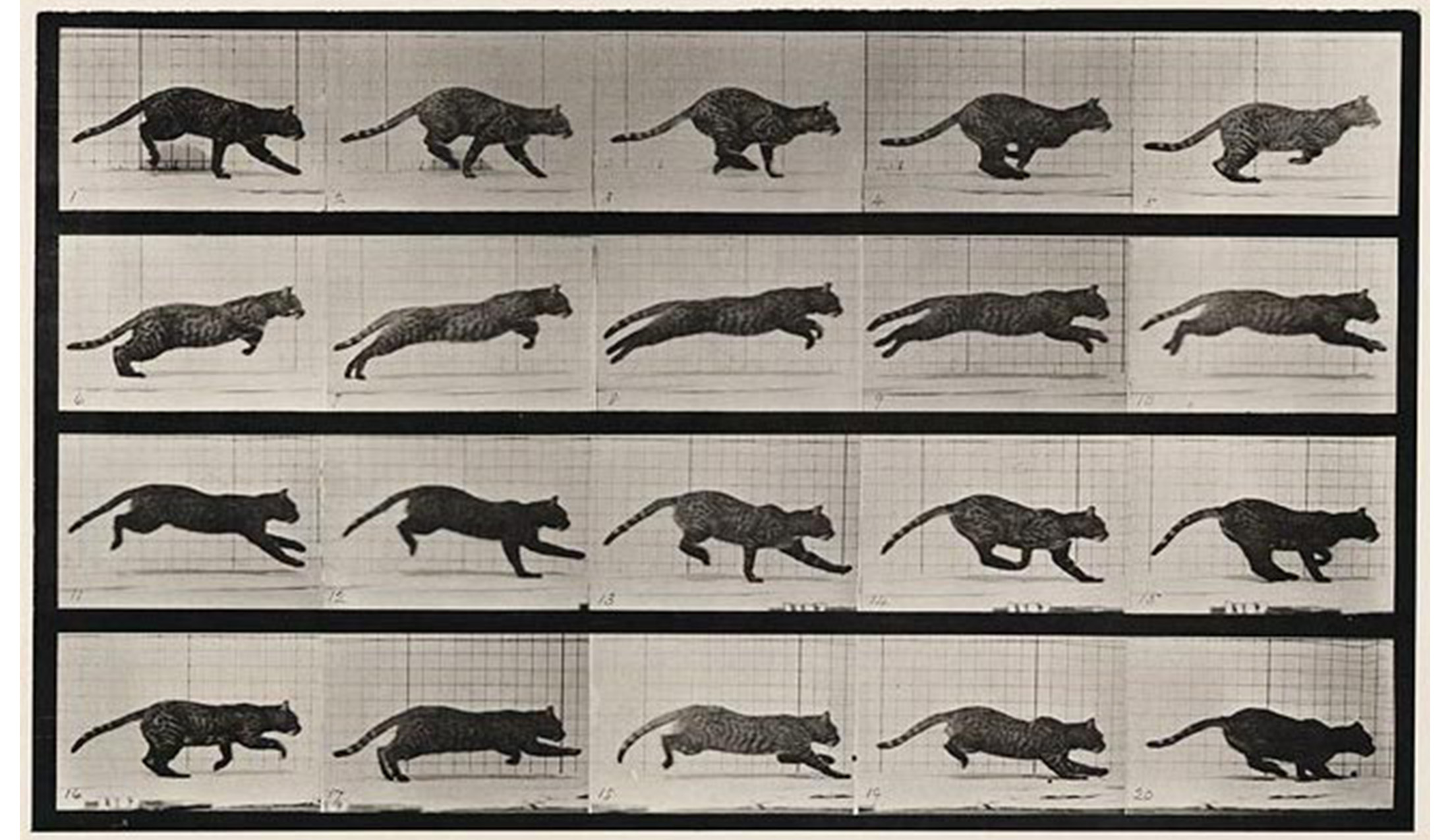

In 1884, Muybridge took a chore at the University of Pennsylvania and began a new project based on his piece of work for Stanford, just expanded his subjects well beyond horses. Muybridge photographed "men, women, and children, animals and birds, all actively engaged in walking, galloping, flight, working, playing, fighting, dancing, or other actions incidental to every-solar day life," (Animal LocomotionProspectus, 1887). He used models, athletes from the university, disabled patients from the local hospital, and animals from the Philadelphia Zoo. Three years afterward, he published his 11 volume masterpieceAnimal Locomotion,which contains 781 plates with 20,000 full photographs. The SCMA has 516 dissimilar plates fromFauna Locomotionin its drove.

Eadweard Muybridge. English, 1830–1904.Creature Locomotion: Plate 365, 1887. Photogravure on newspaper mounted on paperboard. Gift of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1950.53.365.

Eadweard Muybridge. English, 1830–1904.Creature Locomotion: Plate 538, 1887. Photogravure on paper mounted on paperboard. Gift of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1950.53.538.

Muybridge's work revolutionized the fashion scientists studied locomotion and physiology. Previously, scientists were largely limited by what they could discover with their own eyes, especially concerning objects in motility. Before Muybridge took his photographs, there was no style to show Stanford's hypothesis. Muybridge's photographs helped generate new perspectives on the musculature and movements of people and animals.

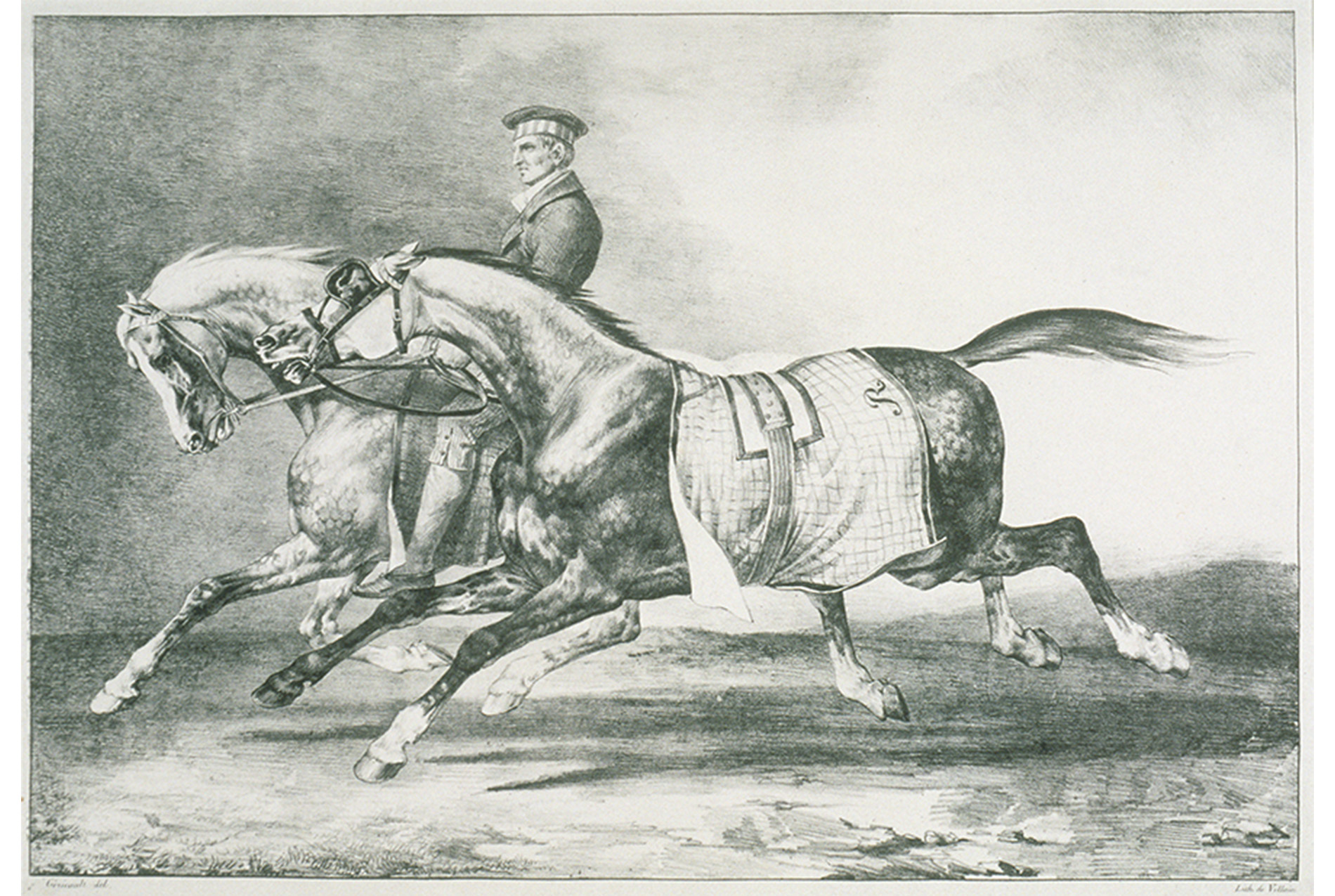

Though the impact of Muybridge'south work was considered to be primarily scientific, at that place was a less obvious but as important bear upon on the creative globe. Many artists, including Edgar Degas, began copying poses from Muybridge's photos to ensure accurateness in their own work. Before Muybridge, artists usually drew horses running with both forelegs extended every bit forward and hind legs as behind, as in the Géricault print pictured below, which looks more than like a cat leaping. Though about artists embraced the new technology and the accuracy it afforded, others such as Baronial Rodin thought that it simply widened the gap between art and science. In his view, Muybridge's piece of work, and photography in general, fell on the side of scientific discipline because it stopped time unnaturally, while art was the synthesis of more than than a single moment.

Théodore Géricault and Eugene Louis Lami. French. Gericault: 1791–1824; Lami: 1800–1890.Ii Dapple-Gray Horses Being Taken for a Walk, 1822. Lithograph on chine collé on paper. Gift of Frederick H. Schab. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1973.33.

Eadweard Muybridge. English language, 1830–1904.Animal Locomotion: Plate 719, 1887. Photogravure on paper mounted on paperboard. Gift of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1950.53.719.

Muybridge considered himself first and foremost, an artist. This was conspicuously demonstrated in his habit of calculation or subtracting photographs in a serial to create more aesthetically pleasing results. Though he buried all the negatives, some collotypes remain today that indicate changes fabricated earlier the terminal printing (for examples and more information, delight visit the National Museum of American History website: https://americanhistory.si.edu/muybridge/alphabetize.htm). Despite his alterations, Muybridge's piece of work revolutionized the way the world understood the motility of animals and is withal an important resource for the study of the body in motion.

0 Response to "Published Animal Locomotion and Paved the Way for Motion Photography"

Post a Comment